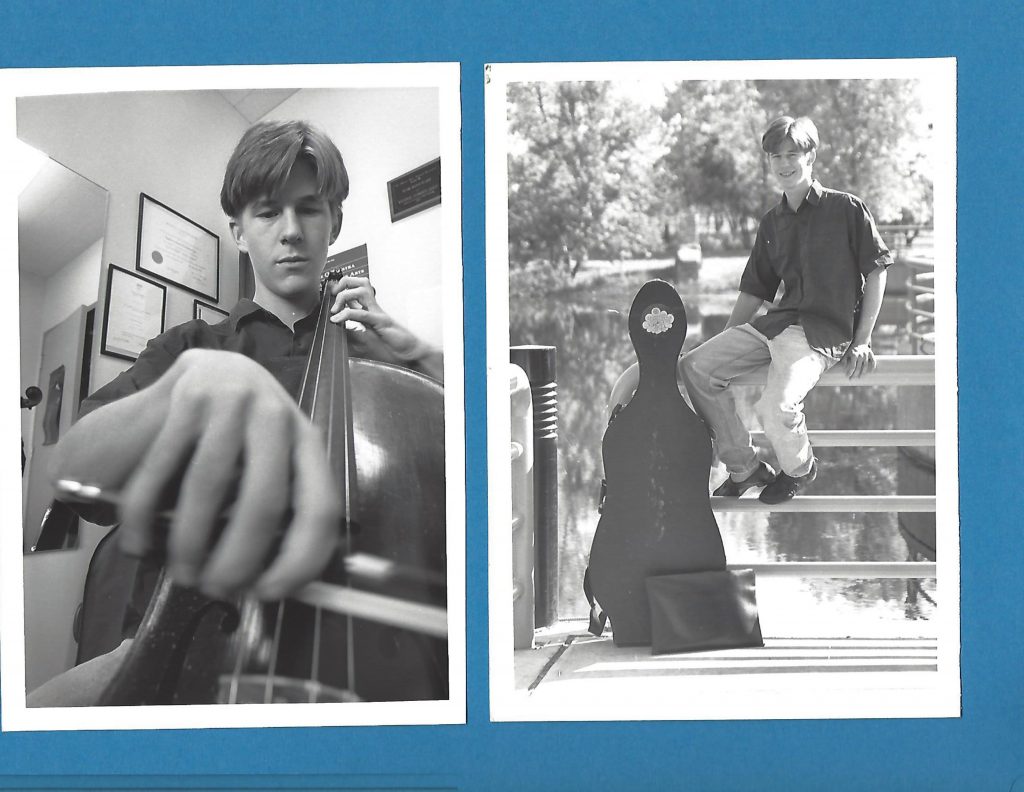

Our youth years are a special, idyllic time in life, generally characterized by unparalleled freedom — one that is short-lived as we experience the inevitable perils of adulthood and its inherited obligations. But at an age when frivolity and nonchalance are justified, Tim Bartsch found himself forfeiting his youthful ways in acceptance of a sobering reality.

“By twenty-one, all my dreams were done,” shares Bartsch. He was an aspiring classical musician at the time, studying abroad at a prestigious arts school, Hochschule fuer Musik Detmold in Germany, when he had to cut his first semester short and return to Canada.

Bartsch was diagnosed with HIV in October 1996 after fleeing from a relationship that he describes as an “abuse of power” with his male cello professor, Robert Bardston who was also HIV positive at the time. Bardston was an esteemed professional in the small community of Medicine Hat, Alberta, and a known advocate for ending HIV/AIDS stigma.

But Bartsch alleges that his former professor, who was 26-years-older than him, was different to his public persona during their intimate relationship. He “broke me down and then tried to raise me back up,” said Bartsch. Speaking sombrely, the soft-spoken 45-year-old claims that he was manipulated into performing sexual acts in exchange for his instructor’s loyalty.

It felt like rape. Years later when reconnecting with him, he told me he was trying to be the macho man he thought turned me on,” Bartsch said.